News Story

A new way to monitor mental health conditions

Tom is under medical care for depression. He takes his medication and sees his clinician at regular intervals. But between visits, he sometimes believes he is getting worse. He feels sluggish, he thinks and talks more slowly, and occasionally the idea of suicide comes into his mind. But he doesn’t want to bother his clinician. He makes it to his next appointment, where his clinician notices the changes and adjusts his medication, but he wonders whether what he experienced between office visits could have been dealt with more quickly.

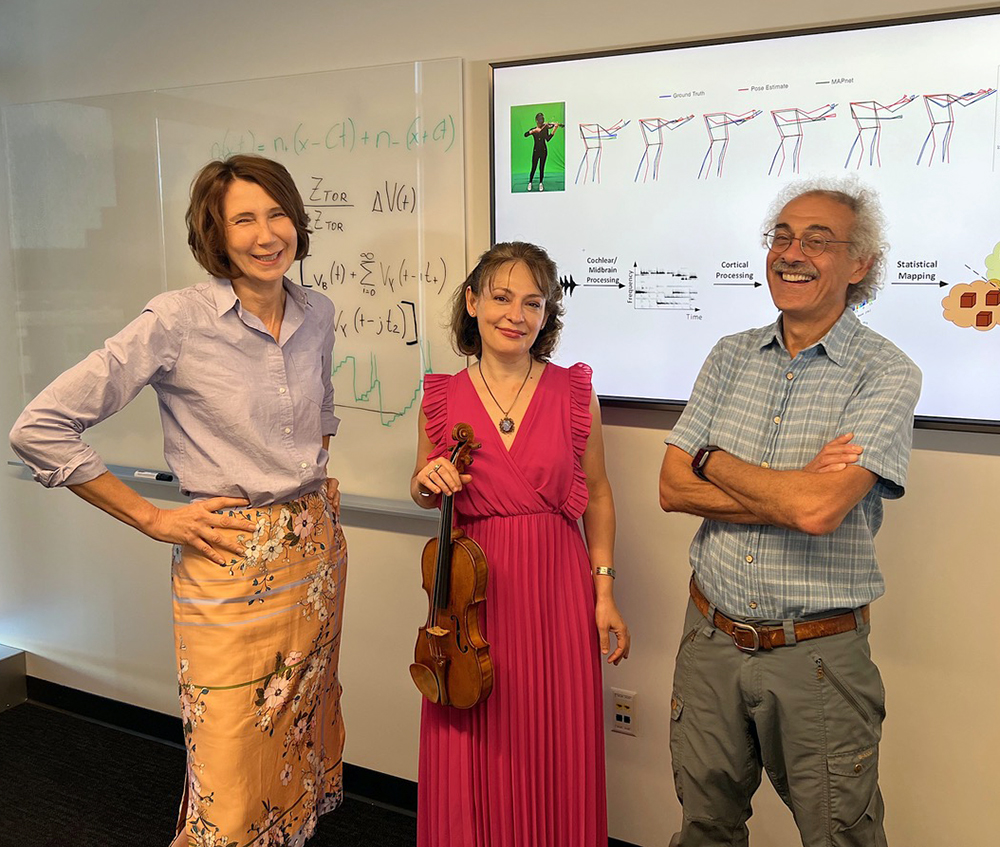

Research by Clark School Professor Carol Espy-Wilson (ECE/ISR) and her team could one day provide help to both Tom and his health care provider through a smart phone app that can detect changes in speech that occur in patients with depression. On June 8, Espy-Wilson gave a keynote address about this work at the 180th meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Mental health issues are an ongoing world crisis. There are far more people with mental illness than there are people who can diagnose and treat them—for example, in the U.S. there is only one mental health clinician for every 30,000 people. Around the world, some 264 million people suffer from depression, the most common precursor to suicide. Unfortunately, currently, a problem like depression can only be diagnosed in a clinical setting.

Even for someone under clinical care, “the time between visits is when many people fall through the cracks and are at increased risk of suicidality,” Espy-Wilson says. “Right now there are not good ways to monitor people’s mental health in between clinical visits.”

From her years of research in signal processing and her expertise in the mechanics of speech production, Espy-Wilson has learned that the complex and neurologically based act of speaking can be a good way to detect and assess mental health issues.

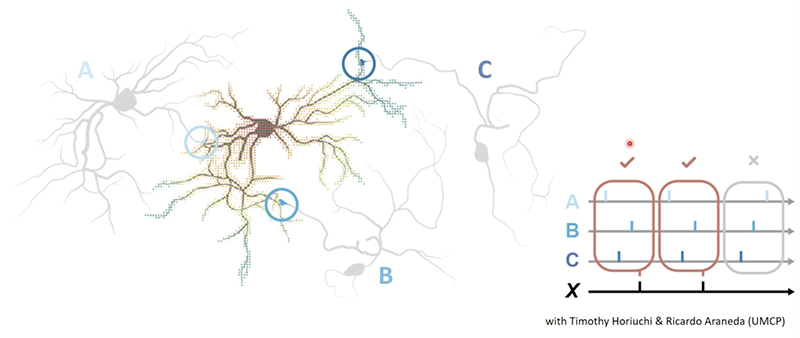

The human speech process requires finely timed coordination to communicate fluently and—seemingly—effortlessly. Articulation consists of an onset, a target, and an offset of sounds. In persons without mental illness these articulators overlap continuously. But when mental illness is present, the way speech is coordinated looks different.

For example, people with depression exhibit “psychomotor slowing,” which tracks with the severity of their condition. This means that depressed people do not think, speak, or move as quickly as those who are not depressed.

“All the gestures of their body slow down,” Espy-Wilson says. “In depression, the articulation coordination of speech is simpler, resulting in slower speech with more and longer pauses. People who are depressed have speech that is less variable than those who are not depressed.”

“This means that if you can reliably detect changes in articulatory coordination, you will have a better chance of making timely and accurate interventions to help patients.”

Espy-Wilson and her team have developed a speech inversion system that uses machine learning technology to convert acoustic signals into articulatory trajectories that can capture changes in speech gesture coordination related to mental health.

Using only the articulatory coordination features of speech, the system can classify depression with an accuracy of 85–90%. It also is able to classify schizophrenia that presents with symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations with 89% accuracy.

The goal is to incorporate this digital health technology system into a smart phone app that patients will find easy to use between visits to their professional. They would be encouraged to use the app for their own health, security and safety. The app would ask the person questions, then use the articulatory markers present in their speech as they reply to alert their clinician to a worsening condition.

“Our hope is that the person would want to use the app regularly, starting when they are feeling fairly well and are more likely to comply,” Espy-Wilson says. “We’d also like the clinician to be able to receive an alert from the app whenever one of their patients seems to be doing poorly.”

To further improve the system’s accuracy, Espy-Wilson is looking to take advantage of other smart phone features such as video, and to incorporate natural language processing capabilities that can detect the actual words a person is using. Video in particular may be especially helpful. In preliminary research using video data from a University of Maryland College Park (UMCP)/University of Maryland Baltimore (UMB) database, adding video to the audio boosted the results by 17%.

“Being able to use the facial gestures will add a lot to the detection of all mental illnesses,” Espy-Wilson says.

In addition, the researchers will increase the system’s sensitivity to the levels of severity of depression and schizophrenia, and will fine-tune it to the speaking patterns of individuals, and changes that occur over time. Eventually they believe they will be able to expand the app’s capabilities to detect other mental illnesses such as anxiety disorder and bipolarism.

A proposal has been submitted to NSF for funding to conduct simulations, the next phase of the research. If approved, Espy-Wilson will be partnering with Professor Philip Resnik (UMIACS/Linguistics), Assistant Professor John Dickerson (UMIACS/CS) and Professor Deanna Kelly (Psychiatry) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSoM). Kelly is director and chief of the Treatment Research Program at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. Pending additional funding, this phase will be followed by a clinical trial.

This set of four researchers already has received two rounds of funding from UMCP/UMSoM AIM-HI seed grants. The funding partially supported the work of Espy-Wilson’s graduate students Nadee Seneviratne, whose Ph.D. work involves the development of a depression classification system; and Yashish Maduwantha, H.P.E.R.S., who is working on a classification system for schizophrenia.

If all goes well, the app will become available for use by clinicians and their patients, and begin making a difference in the way depression is treated.

Published June 14, 2021